The amygdala, a pair of almond-shaped nuclei located deep within the temporal lobes, plays a pivotal role in the processing and memory of emotionally salient events. Its influence extends far beyond the immediate experience of fear, subtly or overtly shaping how individuals encode, store, and retrieve memories. Understanding this intricate relationship offers crucial insights into both typical and atypical memory function, impacting fields from clinical psychology to neuroscience and education. This article delves into the multifaceted impact of the amygdala’s threat response on memory, exploring the biological mechanisms at play and their behavioral consequences.

The amygdala is a central command center for emotional processing, particularly in response to perceived threats. Its strategic location within the limbic system, a network of brain structures implicated in emotion, motivation, and memory, positions it perfectly to mediate the interplay between emotional arousal and cognitive faculties. Its function extends beyond a simple “fear center,” encompassing a broader spectrum of emotional salience. You can watch the documentary about the concept of lost time to better understand its impact on our lives.

Anatomy and Connectivity

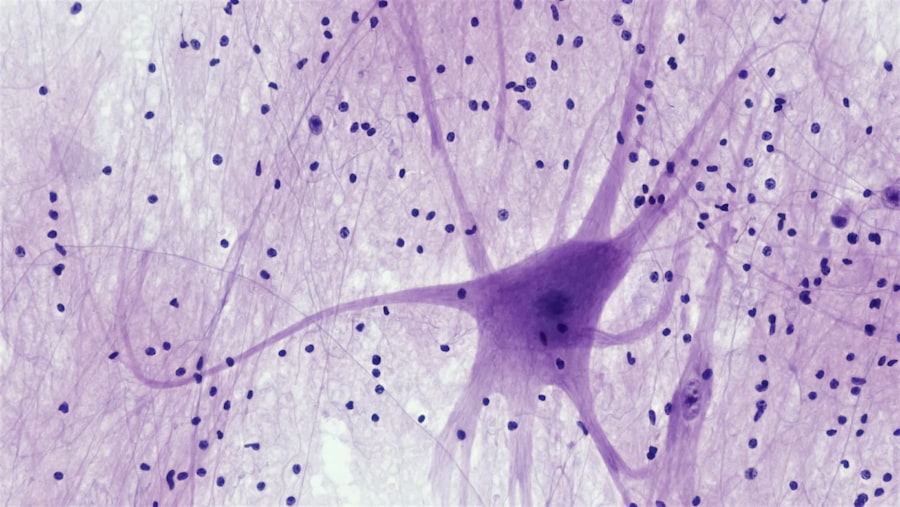

The amygdala is not a monolithic structure but rather a complex of several distinct nuclei, each contributing to its overall function. The basolateral complex (BLA), centered around the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei, is particularly crucial for the acquisition and expression of conditioned fear. This complex receives sensory input from the thalamus and cortex, allowing it to quickly assess the emotional significance of stimuli. The central nucleus (CeA), on the other hand, acts as the primary output region, sending projections to brainstem areas that control physiological responses to threat, such as increased heart rate and respiration, as well as to areas involved in freezing and startle reflexes.

The Threat Detection Circuitry

When an individual encounters a potential threat, sensory information rapidly travels to the amygdala via two primary pathways: the “low road” and the “high road.” The low road, a rapid and crude pathway, projects directly from the thalamus to the amygdala, bypassing cortical processing. This allows for an immediate, albeit less precise, assessment of danger, triggering a rudimentary threat response before conscious awareness. Imagine a sudden rustle in the bushes; the low road instantly primes the body for action, a primeval survival mechanism. Conversely, the high road routes sensory information through the sensory cortex before reaching the amygdala. This pathway provides a more detailed, contextualized analysis of the threat, allowing for a more nuanced and informed response. Consider observing the same rustle, but then identifying it as a harmless bird—the high road allows for this corrective interpretation.

The amygdala plays a crucial role in the threat response and the formation of memories associated with fear and danger. A related article that delves deeper into this topic can be found at XFile Findings, where researchers explore how the amygdala interacts with other brain regions to influence emotional memory and behavioral responses to threats. This article provides valuable insights into the neurobiological mechanisms underlying our reactions to perceived dangers and the lasting impact of these experiences on memory.

Amygdala Activation and Memory Modulation

The amygdala’s activation during a threat response profoundly influences the processes of memory formation, consolidation, and retrieval. This influence is not limited to explicit, declarative memories (facts and events) but also extends to implicit, non-declarative memories (skills and habits). The enhanced memory for emotionally significant events is a testament to the amygdala’s powerful modulatory role.

Enhanced Encoding

The presence of emotional arousal, particularly fear or stress, during an event leads to an increased likelihood of that event being encoded into long-term memory. This phenomenon, often termed “emotional memory enhancement,” is largely mediated by the amygdala. The amygdala, when activated by threat, releases neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine and acetylcholine, which project to other brain regions involved in memory formation, most notably the hippocampus. These neurochemical signals enhance synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus, essentially making the “recording” of the experience more robust. Think of it as highlighting the most important passages in a book – the amygdala is the internal highlighter that marks emotionally salient events for special attention.

Consolidation and Storage

Memory consolidation, the process by which unstable initial memories are transformed into more stable, long-term representations, is also significantly impacted by amygdala activity. During periods of high emotional arousal, the amygdala modulates the activity of the hippocampus during the process of consolidation. Studies have shown that fear-related memories, due to this amygdala-driven modulation, are often retained with greater vividness and detail than neutral memories. This effect is particularly pronounced during sleep, where the amygdala continues to influence the replay of emotional experiences, further strengthening their long-term storage.

Retrieval Bias

The amygdala’s influence doesn’t cease once memories are consolidated; it also plays a role in their retrieval. During retrieval, the amygdala can facilitate the recall of emotionally charged memories, making them more accessible and vivid. Conversely, it can also inhibit the retrieval of neutral memories when an individual is in a state of high emotional arousal or stress, a phenomenon known as “state-dependent memory.” This means that individuals might find it easier to recall fear-inducing experiences when they are experiencing similar emotional states.

The Neuromodulatory System and Memory

The amygdala’s impact on memory is not a solitary endeavor but rather a symphony played by various neuromodulatory systems that it orchestrates. These systems, when activated by the amygdala, fine-tune the processes of memory formation and retrieval.

Noradrenergic System

One of the most critical neuromodulators involved in amygdala-mediated memory enhancement is norepinephrine. When a threat is perceived, the amygdala activates the locus coeruleus, a brainstem nucleus that is the primary source of norepinephrine in the brain. The release of norepinephrine, particularly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, strengthens synaptic connections, leading to improved memory encoding and consolidation. This neuromodulation acts like a volume knob, turning up the intensity of memory formation for emotionally significant events.

Glucocorticoids

Stress hormones, particularly glucocorticoids like cortisol, also play a crucial role. The amygdala directly influences the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to the release of these hormones. While acute, moderate levels of glucocorticoids can enhance memory, chronic or excessively high levels can impair it, particularly in the hippocampus. This biphasic effect highlights the delicate balance of the stress response on cognitive function. Imagine a perfectly warmed oven for baking a cake – too little heat leaves it undone, too much burns it; similarly, optimal glucocorticoid levels are required for memory function.

Acetylcholine

Acetylcholine, another important neurotransmitter, also contributes to the amygdala’s influence on memory. The amygdala projects to the basal forebrain cholinergic system, which in turn releases acetylcholine throughout the cortex and hippocampus. Acetylcholine is critical for attentional processes and synaptic plasticity, further contributing to the enhanced encoding of emotionally salient information.

Maladaptive Memory Formation and Clinical Implications

While the amygdala’s threat response is crucial for survival, its dysregulation can lead to maladaptive memory formation, contributing to various psychological disorders. Understanding these mechanisms is vital for developing effective therapeutic interventions.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Perhaps the most prominent example of maladaptive memory formation linked to amygdala dysfunction is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Individuals with PTSD often experience intrusive and vivid re-experiencing of traumatic events, known as flashbacks. Research suggests that an overactive amygdala, coupled with impaired prefrontal cortex regulation, contributes to the persistent and exaggerated fear response associated with these traumatic memories. The amygdala essentially keeps these traumatic memories on “high alert,” making them easily triggered and difficult to extinguish.

Phobias and Anxiety Disorders

Similar to PTSD, phobias and other anxiety disorders often involve an overgeneralized fear response linked to an aversive experience. The amygdala’s critical role in fear conditioning means that a single traumatic event, even one not objectively life-threatening, can lead to the formation of powerful, persistent fear memories. These memories are often resistant to extinction, as the amygdala drives a strong avoidance response, preventing new, non-threatening associations from being formed.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

While not as directly linked to explicit fear memories, the amygdala’s involvement in emotional processing also plays a role in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). The emotional salience attributed to certain thoughts or actions, often accompanied by feelings of anxiety or disgust, can lead to repetitive behaviors aimed at alleviating this distress. The amygdala’s contribution to the emotional weight of these intrusive thoughts and the subsequent compulsion to perform rituals highlights its broad influence on emotional drives and their impact on cognitive processes.

Research into the amygdala’s role in threat response and memory has revealed fascinating insights into how our brains process fear and danger. A related article discusses the intricate mechanisms behind this emotional response and how it influences our behavior in stressful situations. For a deeper understanding of these concepts, you can read more in this informative piece found at this link. Exploring these connections can shed light on the broader implications of emotional memory and its impact on mental health.

Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Amygdala-Mediated Memory

| Metric | Description | Typical Value/Range | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amygdala Activation Level | Degree of neural activity in the amygdala during threat exposure | Increased BOLD signal by 10-30% compared to baseline | fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) |

| Memory Retention Rate | Percentage of threat-related memories retained after 24 hours | 60-80% | Behavioral recall tests |

| Fear Conditioning Response | Physiological response (e.g., skin conductance) to conditioned threat stimuli | Increase of 0.5-2 µS in skin conductance | Skin conductance response (SCR) measurement |

| Synaptic Plasticity Markers | Levels of proteins associated with synaptic changes in the amygdala (e.g., BDNF) | Upregulation by 20-50% post-threat exposure | Western blot or immunohistochemistry |

| Stress Hormone Levels | Cortisol concentration during threat memory encoding | 10-25 µg/dL (elevated from baseline) | Saliva or blood assay |

Given the amygdala’s central role in maladaptive memory formation, therapeutic interventions often target its activity and the pathways it influences. These approaches aim to modify the emotional valence of memories or to weaken the fear associations.

Exposure Therapy

Exposure therapy, a cornerstone of treatment for anxiety disorders and PTSD, directly addresses amygdala-mediated fear responses. By gradually and repeatedly exposing individuals to feared stimuli in a safe and controlled environment, therapists aim to extinguish the conditioned fear response. This process, known as fear extinction, is thought to involve the formation of new, inhibitory memories in the prefrontal cortex that suppress the amygdala’s fear output. Essentially, the individual learns that the previously feared stimulus is no longer threatening, re-writing the emotional script associated with the memory.

Pharmacological Interventions

Pharmacological interventions, such as beta-blockers and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), can also modulate amygdala activity. Beta-blockers, when administered shortly after a traumatic event, have shown promise in preventing the consolidation of traumatic memories by reducing the effects of norepinephrine on the amygdala. SSRIs, by increasing serotonin levels, can help to regulate amygdala activity and reduce overall anxiety, thereby making individuals more receptive to cognitive and behavioral therapies.

Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive restructuring, a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), focuses on identifying and challenging maladaptive thought patterns associated with emotional memories. While not directly targeting the amygdala’s physiological activity, it aims to reframe the interpretation of emotionally charged events, thereby altering their emotional impact. By changing the narrative surrounding a traumatic memory, individuals can lessen its power and reduce the amygdala’s automatic fear response. This is akin to editing a script, changing the dramatic ending to a less terrifying one.

In conclusion, the amygdala’s profound influence on memory extends across all phases of memory formation, from initial encoding to long-term retrieval. Its role as a crucial threat detector and emotional modulator ensures that emotionally significant events, particularly those involving threat, are prioritized and etched deeply into an individual’s mental landscape. While this adaptive mechanism is essential for survival, its dysregulation can lead to the enduring and debilitating emotional memories characteristic of various psychological disorders. By unraveling the complex interplay between the amygdala and other memory systems, researchers and clinicians continue to advance our understanding of memory and develop more effective strategies for mitigating the impact of traumatic and maladaptive emotional experiences. Addressing the amygdala’s threat response offers a significant pathway to alleviating suffering and improving mental well-being.

WATCH THIS 🔥LOST 8 HOURS: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You About Missing Time

FAQs

What is the amygdala and what role does it play in threat response?

The amygdala is a small, almond-shaped structure located deep within the brain’s temporal lobe. It plays a crucial role in processing emotions, particularly fear and threat detection. The amygdala helps initiate the body’s threat response by activating physiological reactions such as increased heart rate and release of stress hormones.

How does the amygdala contribute to memory formation related to threats?

The amygdala is involved in encoding and consolidating emotional memories, especially those associated with fear or danger. When a threat is perceived, the amygdala interacts with other brain regions like the hippocampus to strengthen the memory of the event, making it more vivid and easier to recall in the future.

Can the amygdala’s threat response affect behavior?

Yes, the amygdala’s activation during a threat can influence behavior by triggering fight, flight, or freeze responses. It can also lead to heightened vigilance and avoidance behaviors to protect an individual from potential harm based on past experiences.

Is the amygdala’s threat response always accurate?

No, the amygdala can sometimes respond to perceived threats that are not actually dangerous, leading to false alarms or exaggerated fear responses. This can contribute to anxiety disorders or phobias when the threat response is disproportionate to the actual situation.

Can the amygdala’s threat response be modified or regulated?

Yes, the amygdala’s response to threats can be regulated through various methods such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, and stress reduction techniques. These approaches can help reduce excessive fear responses and improve emotional regulation by influencing amygdala activity and its connections with other brain regions.