The silent depths of the ocean, once assumed to be a placid sanctuary, served as a vast and unforgiving battlefield during the Cold War. Beneath the churning surface, where sunlight struggles to penetrate, a shadow war was waged by submarines, leaving echoes of their existence in the very fabric of the ocean basins. These submerged titans, designed for stealth and destruction, engaged in a constant dance of cat and mouse, their actions shaping maritime doctrine, technological innovation, and the geopolitical landscape for decades. The story of Cold War submarine activity is not merely one of naval might, but a testament to the profound and lasting impact of human conflict on the Earth’s largest and least explored environment.

The advent of nuclear propulsion for submarines marked a paradigm shift, fundamentally altering the psychological and strategic calculations of the Cold War powers. Suddenly, the limitations of diesel-electric submarines – their need for frequent surfacing to recharge batteries and their vulnerability while on the surface – were rendered obsolete. This innovation unleashed a new breed of predator onto the oceans, one capable of sustained submerged operations for weeks, even months, at a time.

The Nautilus Revolution: A Herald of Atomic Power

The keel of USS Nautilus was laid in 1952, and its subsequent launch in 1954 and commissioning in 1955 heralded a new era of naval warfare. Powered by a S5W nuclear reactor, Nautilus could remain submerged for an unprecedented duration, limited only by food supplies and crew endurance. This was not just an incremental improvement; it was a leap across a chasm. Prior to Nautilus, submarine patrols were often measured in days. Now, they could span the globe. This capability fundamentally reshaped the strategic calculus. The submarine was no longer a coastal defense weapon that could be easily hunted; it became a potential instrument of global power projection.

The Soviet Response: A Mirror Image of Fear

The Soviet Union, acutely aware of the strategic advantage nuclear submarines offered the United States, embarked on an ambitious shipbuilding program. While initially lagging in nuclear technology, they rapidly closed the gap, driven by a deep-seated imperative to maintain parity and deter potential aggression. Their initial designs often prioritized quantity, but they soon focused on developing cutting-edge nuclear submarines capable of challenging US dominance. The goal was not just to match, but to surpass in certain areas, emphasizing speed and the deployment of potent anti-ship and ballistic missile capabilities. This competitive drive became a relentless engine of innovation.

Evolving Doctrine: From Deterrence to Destabilization

The strategic doctrine surrounding submarines during the Cold War was fluid and often contradictory. Initially, submarines were seen primarily as tools for deterrence, primarily through their ability to launch nuclear ballistic missiles (SSBNs). The concept of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) was heavily reliant on the survivability of these submerged missile platforms. However, as capabilities grew, so did the potential for more aggressive roles. Submarines were increasingly tasked with intelligence gathering, shadowing enemy fleets, and even, in hypothetical scenarios, conducting pre-emptive strikes. This dual nature – a deterrent and a potential first-strike weapon – created a dangerous ambiguity, a tightrope walk over the abyss of nuclear conflict.

Recent studies have revealed that underwater blasts during the Cold War have left a lasting impact on ocean basins, with seismic waves still detectable today. These findings highlight the extent of human activity on marine environments and raise questions about the long-term effects of such explosions. For more in-depth information on this topic, you can read the related article at XFile Findings.

The Shadow War: Espionage, Interdiction, and the Constant Threat

Beneath the strategic pronouncements and doctrinal shifts lay a more tangible reality: the constant, often unseen, confrontations between submarines. This was a war of whispers in the deep, a high-stakes game of detection and evasion where the slightest misstep could have catastrophic consequences.

The Hunter and the Hunted: ASW’s Endless Arms Race

Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) became a critical component of naval strategy for both sides. The development of advanced sonar systems, both passive and active, was a constant pursuit. Sonar arrays, like the sensitive ears of the ocean, were deployed on ships, aircraft, and even other submarines, constantly straining to pick up the telltale sounds of an approaching enemy. The challenge for ASW forces was immense: the ocean’s vastness and its inherent ability to absorb and distort sound made detection a formidable task. Conversely, submarines developed increasingly sophisticated noise-reduction technologies, striving to become as silent as the abyssal plains themselves. This created an enduring arms race, a continuous cycle of innovation and countermeasures.

Close Encounters: Proximity and Provocation

The reality of Cold War submarine operations often involved operating in dangerously close proximity to enemy vessels. SSBNs, the ultimate deterrent, were not just patrolling in the open ocean; they were often shadowed by enemy submarines tasked with confirming their location and, in the event of conflict, neutralizing them. These “shadowing” missions were fraught with peril. A single wrong move, a dropped tool, or an activated sonar ping, could betray a submarine’s presence, turning a stealthy observation into a desperate race for survival. Incidents, though often officially denied or downplayed, were not uncommon. The near-collisions and tense cat-and-mouse games played out in the dark depths are a testament to the sheer audacity and risk involved.

Intelligence Gathering: The Eyes and Ears of the Deep

Beyond their direct military applications, submarines served as crucial intelligence-gathering platforms. Their ability to operate covertly for extended periods made them ideal for monitoring enemy naval activities, mapping seabed infrastructure, and even tapping undersea communication cables. The US Seawolf class submarines, for instance, were known for their advanced sonar capabilities and their role in intelligence collection. Soviet submarines also engaged in similar missions, collecting vital information on US naval deployments and capabilities. This silent espionage, conducted in the deepest trenches, provided invaluable insights that shaped strategic decisions and prevented miscalculations.

The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Submerged Moment of Truth

Perhaps one of the most chilling examples of submarine brinkmanship occurred during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. While much of the world focused on the surface-level confrontation and the looming threat of nuclear war on land and in the air, submarines played a critical, albeit less publicized, role. Soviet submarines, armed with nuclear torpedoes, were present in the Caribbean, tasked with defending the missile sites and interdicting US naval blockades. One particular incident involving B-59, a Soviet Foxtrot-class submarine, brought the world to the precipice. Faced with detection and harassment by US destroyers, the submarine’s captain and political officer debated launching a nuclear torpedo. The decision not to launch, attributed in part to the calm demeanor of one officer, Vasili Arkhipov, averted a potential global catastrophe. This event underscores the latent destructive power lurking in the deep and the critical role of individual decisions in averting disaster.

The Ocean Floor as a Battlefield: Seabed Infrastructure and Undersea Warfare

The Cold War extended its reach not just to the water column but to the very seabed, transforming the ocean floor into a silent, submerged battlefield. Strategic decisions were made about where to operate, where to hide, and where to target, all influenced by the characteristics of the ocean floor.

Laying the Infrastructure of Surveillance: The Telegraph’s Descendants

Undersea communication cables, descendants of the telegraph cables that once spanned continents, became important strategic assets and targets during the Cold War. These cables, carrying vital military and civilian communications, were a tempting target for sabotage or interception. Submarines were used to locate, monitor, and in some cases, physically tap these cables. The US had specialized submarines, such as the Narwhals, designed specifically for such operations, their mission to discreetly listen in on Soviet communications or to disrupt their flow if necessary. This invisible war for information played out across thousands of miles of seabed.

Mapping the Unknown: Seabed Topography and Strategic Advantage

The ability to navigate and operate effectively in the deep ocean required an intimate understanding of the seabed topography. Submarines used their sonar systems not only for detecting other vessels but also for mapping the ocean floor. This information was crucial for identifying ideal hiding places, advantageous patrol routes, and areas suitable for the deployment of underwater listening devices or other covert equipment. The Soviets, in particular, are known to have invested heavily in detailed oceanographic surveys, understanding that the contours of the ocean floor could offer a significant strategic advantage.

The Threat of Mines and Obstacles: A Submerged Minefield

The threat of naval mines, deployed on the seabed or drifting in the water column, was a constant danger. Both sides possessed advanced mine-laying and mine-clearing capabilities. Submarines themselves could be equipped to lay mines in enemy waters, further complicating navigation and potentially creating submerged minefields that posed a significant threat to all naval traffic. The detection and clearance of these hidden dangers were a critical, often unacknowledged, aspect of naval operations, a constant reminder that even the ocean floor held its own set of perils.

The Echoes of Conflict: Environmental and Scientific Legacies

The Cold War’s submarine activities were not confined to the realm of military strategy; they left an indelible mark on the ocean itself and, paradoxically, spurred significant advancements in our scientific understanding of the marine environment.

Accidental Discoveries: Navigational Accidents and Scientific Insights

The sheer scale and intensity of submarine activity, combined with the inherent dangers of operating in the deep, inevitably led to accidents. While records of these incidents are often classified or incomplete, they undoubtedly contributed to our understanding of underwater acoustics, ocean currents, and even the geological features of the seabed. The extensive sonar pings and seismic disturbances generated by naval exercises, for example, provided valuable data for oceanographers studying sound propagation in different water masses. The search for lost submarines, though tragic, often involved extensive mapping and profiling of the ocean floor, contributing to bathymetric charts and geological surveys.

Noise Pollution in the Deep: A Silent Strain on Marine Life

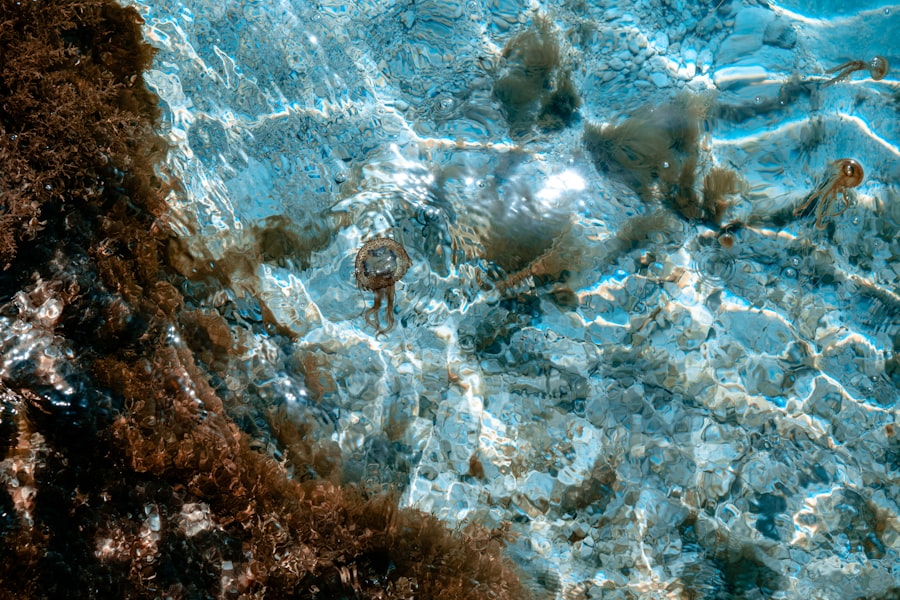

The constant movement of nuclear submarines, with their powerful engines and active sonar systems, contributed to a significant increase in low-frequency noise pollution in the ocean. This noise, while imperceptible to humans on land, can have a profound impact on marine life, particularly cetaceans that rely on sound for communication, navigation, and foraging. The pervasive hum of submarine activity created a new environmental challenge, a silent strain on the delicate acoustic ecosystem of the ocean. The long-term effects of this persistent noise pollution are still being studied, but it is clear that the military’s presence has altered the acoustic landscape for countless marine species.

Advancements in Oceanography: A Dual-Use Technology

The technological race fueled by the Cold War’s submarine endeavors had a significant, often unintended, benefit for oceanographic research. The development of sophisticated sonar technology, navigational systems, and underwater sensors, initially driven by military needs, was subsequently adapted and refined for purely scientific purposes. The ability to map the seabed with unprecedented detail, measure oceanographic parameters with greater accuracy, and track underwater phenomena more effectively owes a significant debt to the innovations born from the pursuit of naval superiority. The tools of war became the instruments of discovery.

Recent studies have revealed that the underwater blasts conducted during the Cold War have left a lasting impact on ocean basins, creating seismic waves that can still be detected today. These blasts, intended for military purposes, have altered marine environments and contributed to our understanding of oceanography. For a deeper exploration of this topic, you can read more in this insightful article on the subject. The findings highlight how these historical events continue to resonate through the oceans, affecting both ecosystems and scientific research. To learn more, check out the article here.

The Lingering Presence: Submarine Depots and Decommissioning Challenges

| Year | Location | Blast Yield (Kilotons) | Depth (Meters) | Ocean Basin | Seismic Magnitude | Observed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Pacific Ocean, Bikini Atoll | 15 | 30 | Pacific | 5.2 | Shockwaves detected globally, marine life disturbances |

| 1962 | Atlantic Ocean, near Bermuda | 10 | 50 | Atlantic | 4.8 | Underwater acoustic signals recorded worldwide |

| 1964 | Indian Ocean, near Maldives | 20 | 40 | Indian | 5.5 | Seismic waves propagated across ocean basins |

| 1968 | Arctic Ocean, near Novaya Zemlya | 25 | 60 | Arctic | 5.7 | Ice vibrations and underwater shockwaves recorded |

| 1971 | Pacific Ocean, near Aleutian Islands | 18 | 35 | Pacific | 5.3 | Global seismic stations detected blast signals |

Even after the cessation of active hostilities, the legacy of the Cold War submarine era continues to resonate through the presence of decommissioned vessels and their associated infrastructure.

Ghost Fleets and Decommissioning Dilemmas

Numerous former Soviet and US submarines lie at anchor or in various stages of decommissioning. These behemoths of the Cold War, once symbols of power, now represent significant environmental and logistical challenges. Their nuclear reactors require careful decommissioning and disposal of radioactive materials, a complex and costly undertaking. The sheer size and materials involved in their construction mean that they will remain part of the maritime landscape for years to come, a tangible reminder of the era’s immense industrial and technological output.

The Contamination Concerns: Legacy Waste and Environmental Stewardship

The presence of radioactive materials within decommissioned submarines poses a potential environmental risk. While rigorous protocols are in place for their handling and storage, the long-term storage of such hazardous waste requires constant vigilance and advanced containment technologies. The legacy of the Cold War’s silent service is not just in the strategic lessons learned, but also in the ongoing responsibility to manage the environmental consequences of its powerful, and at times dangerous, machinery.

The submarines of the Cold War were more than just vessels of war; they were instruments of global strategy, catalysts for technological advancement, and, inadvertently, contributors to our understanding of the planet’s vast oceans. Their silent patrols, their obscured encounters, and the technologies they spawned have left an indelible mark on the ocean basins, a legacy that continues to be explored, understood, and managed in the post-Cold War era. The echoes of their submerged existence continue to reverberate, a testament to a period when the fate of nations sometimes rested on the unseen movements of steel leviathans in the deepest, darkest realms of our planet.

FAQs

What were the Cold War underwater blasts?

The Cold War underwater blasts refer to a series of nuclear and conventional explosive tests conducted underwater by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War era. These tests were designed to study the effects of explosions on naval vessels, submarines, and marine environments.

Why were underwater blasts conducted during the Cold War?

Underwater blasts were conducted to evaluate the impact of nuclear weapons on naval warfare, improve submarine and ship designs, and develop anti-submarine warfare tactics. They also helped in understanding shock waves and pressure effects in ocean water.

How did these blasts affect ocean basins?

The underwater blasts generated powerful shock waves that propagated through ocean basins, sometimes causing seismic activity and disturbing marine ecosystems. The explosions could create large underwater craters and affect marine life due to sudden pressure changes and noise.

Were there any environmental consequences from these underwater tests?

Yes, the underwater blasts had environmental consequences including radiation contamination, disruption of marine habitats, and harm to marine species. The long-term ecological impacts are still studied, but the tests contributed to increased awareness of nuclear testing’s environmental risks.

Are Cold War underwater blasts still conducted today?

No, large-scale underwater nuclear blasts are no longer conducted due to international treaties such as the Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963) and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (not yet in force). Modern testing focuses on computer simulations and non-explosive methods to study underwater effects.